Which Would Be A Positive Externality Of A Landscaperã¢â‚¬â„¢s Service For An Individual Homeowner?

In economics, an externality is an indirect cost or benefit to an uninvolved 3rd political party that arises as an effect of another party's (or parties') activity. Externalities tin can be considered equally unpriced goods involved in either consumer or producer marketplace transactions. Air pollution from motor vehicles is i case. The cost of air pollution to society is not paid by either the producers or users of motorized send to the rest of society. Water pollution from mills and factories is some other instance. We are all made worse off by pollution merely are not compensated by the market for this damage. A positive externality is when an individual's consumption in a market increases the well-being of others, but the individual does non charge the third party for the benefit. The 3rd party is essentially getting a free product. An case of this might be the apartment in a higher place a baker receiving the benefit of enjoyment from smelling fresh pastries every morning time. The people who alive in the flat do not compensate the bakery for this do good. [1]

The concept of externality was commencement developed by economist Arthur Pigou in the 1920s.[two] The prototypical instance of a negative externality is environmental pollution. Pigou argued that a tax, equal to the marginal damage or marginal external cost, (afterwards called a "Pigouvian tax") on negative externalities could exist used to reduce their incidence to an efficient level.[2] Subsequent thinkers have debated whether it is preferable to tax or to regulate negative externalities,[3] the optimally efficient level of the Pigouvian taxation,[4] and what factors crusade or exacerbate negative externalities, such as providing investors in corporations with limited liability for harms committed by the corporation.[5] [half-dozen] [7]

Externalities ofttimes occur when the product or consumption of a product or service's individual cost equilibrium cannot reflect the true costs or benefits of that product or service for gild equally a whole.[8] [9] This causes the externality competitive equilibrium to not adhere to the condition of Pareto optimality. Thus, since resource can be meliorate allocated, externalities are an example of market failure.[ten]

Externalities can be either positive or negative. Governments and institutions often take actions to internalize externalities, thus marketplace-priced transactions tin can incorporate all the benefits and costs associated with transactions between economic agents.[11] [12] The most common way this is done is by imposing taxes on the producers of this externality. This is usually done similar to a quote where there is no revenue enhancement imposed and and so once the externality reaches a certain point in that location is a very high tax imposed. However, since regulators do non ever have all the information on the externality it tin can be hard to impose the right revenue enhancement. One time the externality is internalized through imposing a tax the competitive equilibrium is at present Pareto optimal.

For instance, manufacturing activities that cause air pollution impose health and clean-up costs on the whole lodge, whereas the neighbors of individuals who choose to fire-proof their homes may benefit from a reduced adventure of a fire spreading to their ain houses. If external costs exist, such as pollution, the producer may choose to produce more of the product than would exist produced if the producer were required to pay all associated ecology costs. Because responsibility or consequence for self-directed activity lies partly outside the self, an chemical element of externalization is involved. If there are external benefits, such as in public safety, less of the good may be produced than would be the instance if the producer were to receive payment for the external benefits to others.

History of the concept [edit]

2 British economists are credited with having initiated the formal study of externalities, or "spillover effects": Henry Sidgwick (1838–1900) is credited with starting time articulating, and Arthur C. Pigou (1877–1959) is credited with formalizing the concept of externalities.[xiii]

The word externality is used because the effect produced on others, whether in the course of profits or costs, is external to the market.

Definitions [edit]

A negative externality is any difference between the private toll of an action or decision to an economic agent and the social cost. In simple terms, a negative externality is anything that causes an indirect cost to individuals. An example is the toxic gases that are released from industries or mines, these gases cause harm to individuals inside the surrounding area and have to behave a cost (indirect toll) to get rid of that impairment. Conversely, a positive externality is any deviation betwixt the private benefit of an action or decision to an economic amanuensis and the social benefit. A positive externality is anything that causes an indirect benefit to individuals. For example, planting trees makes individuals' property await nicer and information technology also cleans the surrounding areas.

In microeconomic theory, externalities are factored into competitive equilibrium analysis equally the social effect, as opposed to the private marketplace which only factors direct economical effects. The social event of economic activity is the sum of the indirect (the externalities) and directly factors. The Pareto optimum, therefore, is at the levels in which the social marginal do good equals the social marginal toll.[ citation needed ]

Formal definition [edit]

Suppose that there are different possible allocations and unlike agents, where and . Suppose that each agent has a type and that each amanuensis gets payoff , where is the transfer paid past the -th agent. A map is a social option function if

for all An allocation is ex-post efficient if

for all and all

Allow denote an ex-post efficient allocation and let denote an ex-post efficient allocation without agent . Then the externality imposed by agent on the other agents is

- [xiv]

where is the type vector without its -th component. Intuitively, the first term is the hypothetical total payoff for all agents given that agent does not exist, and the 2nd (subtracted) term is the bodily total payoff for all agents given that amanuensis does exist.

Implications [edit]

The implications acquired as a consequence of externalities tin be both positive and negative. If two carve up businesses agree to allow their activities to affect each other than it is mutually beneficial, considering they would not concord to it in the first place if information technology was going to exist damaging to their business. However, other external parties can also be affected by the deal without their cognition or the other businesses' cognition. Unlike the original transaction as the third party did not hold information technology could provide both positive and negative implications.[fifteen]

A voluntary exchange may reduce societal welfare if external costs exist. The person who is affected by the negative externalities in the case of air pollution will run across it as lowered utility: either subjective displeasure or potentially explicit costs, such as college medical expenses. The externality may fifty-fifty be seen as a trespass on their lungs, violating their property rights. Thus, an external price may pose an upstanding or political problem. Negative externalities are Pareto inefficient, and since Pareto efficiency underpins the justification for private holding, they undermine the whole idea of a market economic system. For these reasons, negative externalities are more problematic than positive externalities.[16]

Although positive externalities may appear to be beneficial, while Pareto efficient, they even so represent a failure in the market place as it results in the production of the proficient falling under what is optimal for the market. By assuasive producers to recognise and attempt to command their externalities production would increase equally they would have motivation to do and then.[17] With this comes the Gratis Rider Problem. The Free Passenger Problem arises when people overuse a shared resources without doing their function to produce or pay for it. It represents a failure in the market where appurtenances and services are not able to be distributed efficiently, allowing people to take more than what is off-white. For instance, if a farmer has honeybees a positive externality of owning these bees is that they will likewise pollinate the surrounding plants. This farmer has a next door neighbour who likewise benefits from this externality even though he does not accept whatsoever bees himself. From the perspective of the neighbor he has no incentive to purchase bees himself as he is already benefiting from them at zip cost. But for the farmer, he is missing out on the full benefits of his own bees which he paid for, considering they are also being used by his neighbor.[18]

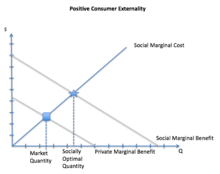

Graph of Positive Externality in Production

There are a number of theoretical ways of improving overall social utility when negative externalities are involved. The market-driven approach to correcting externalities is to "internalize" third party costs and benefits, for case, by requiring a polluter to repair any damage acquired. But in many cases, internalizing costs or benefits is not viable, particularly if the true monetary values cannot be adamant.

Laissez-faire economists such equally Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman sometimes refer to externalities as "neighborhood effects" or "spillovers", although externalities are non necessarily small or localized. Similarly, Ludwig von Mises argues that externalities arise from lack of "clear personal property definition."

Examples [edit]

Externalities may ascend betwixt producers, between consumers or between consumers and producers. Externalities can exist negative when the activeness of one party imposes costs on another, or positive when the action of i party benefits another.

| Consumption | Product | |

| Negative | Negative externalities in consumption | Negative externalities in production |

| Positive | Positive externalities in consumption | Positive externalities in production |

Negative [edit]

Lite pollution is an example of an externality considering the consumption of street lighting has an issue on bystanders that is non compensated for by the consumers of the lighting.

A negative externality (also chosen "external toll" or "external diseconomy") is an economical activeness that imposes a negative upshot on an unrelated 3rd political party. It tin can arise either during the product or the consumption of a skilful or service.[nineteen] Pollution is termed an externality because information technology imposes costs on people who are "external" to the producer and consumer of the polluting product.[20] Barry Commoner commented on the costs of externalities:

Clearly, we take compiled a tape of serious failures in recent technological encounters with the environment. In each instance, the new technology was brought into use before the ultimate hazards were known. We accept been quick to reap the benefits and slow to encompass the costs.[21]

Many negative externalities are related to the ecology consequences of production and utilize. The article on environmental economics too addresses externalities and how they may be addressed in the context of ecology problems.

"The corporation is an externalizing machine (moving its operating costs and risks to external organizations and people), in the same manner that a shark is a killing automobile." - Robert Monks (2003) Republican candidate for Senate from Maine and corporate governance adviser in the motion-picture show "The Corporation".

Negative production externalities [edit]

Examples for negative production externalities include:

Negative production externality

- Air pollution from burning fossil fuels. This activeness causes amercement to crops, materials and (historic) buildings and public health.[22] [23]

- Anthropogenic climate change equally a consequence of greenhouse gas emissions from the called-for of fossil fuels and the rearing of livestock. The Stern Review on the Economic science of Climate Change says "Climatic change presents a unique challenge for economics: information technology is the greatest example of market failure we have ever seen."[24]

- H2o pollution from industrial effluents tin harm plants, animals, and humans

- Spam emails during the sending of unsolicited letters by electronic mail.[25]

- Noise pollution during the production process, which may exist mentally and psychologically disruptive.

- Systemic risk: the risks to the overall economy arising from the risks that the cyberbanking system takes. A condition of moral hazard can occur in the absenteeism of well-designed banking regulation,[26] or in the presence of badly designed regulation.[27]

- Negative furnishings of Industrial farm animal product, including "the increment in the pool of antibiotic-resistant bacteria because of the overuse of antibiotics; air quality problems; the contamination of rivers, streams, and coastal waters with concentrated brute waste; brute welfare problems, mainly as a upshot of the extremely shut quarters in which the animals are housed."[28] [29]

- The depletion of the stock of fish in the ocean due to overfishing. This is an example of a mutual property resource, which is vulnerable to the tragedy of the commons in the absence of advisable environmental governance.

- In the Usa, the cost of storing nuclear waste product from nuclear plants for more than than ane,000 years (over 100,000 for some types of nuclear waste) is, in principle, included in the cost of the electricity the plant produces in the form of a fee paid to the government and held in the radioactive waste superfund, although much of that fund was spent on Yucca Mountain without producing a solution. Conversely, the costs of managing the long-term risks of disposal of chemicals, which may remain chancy on similar time scales, is not commonly internalized in prices. The USEPA regulates chemicals for periods ranging from 100 years to a maximum of 10,000 years.

Negative consumption externalities [edit]

Examples of negative consumption externalities include:

Negative consumption externality

- Noise pollution: Sleep deprivation due to a neighbor listening to loud music late at nighttime.

- Antibiotic resistance, caused by increased usage of antibiotics: Individuals do non consider this efficacy cost when making usage decisions. Government policies proposed to preserve future antibody effectiveness include educational campaigns, regulation, Pigouvian taxes, and patents.

- Passive smoking: Shared costs of failing health and vitality acquired by smoking or alcohol abuse. Hither, the "cost" is that of providing minimum social welfare. Economists more frequently attribute this problem to the category of moral hazards, the prospect that parties insulated from risk may carry differently from the way they would if they were fully exposed to the take chances. For example, individuals with insurance against machine theft may exist less vigilant about locking their cars, considering the negative consequences of automobile theft are (partially) borne by the insurance visitor.

- Traffic congestion: When more people use public roads, road users experience congestion costs such as more than waiting in traffic and longer trip times. Increased route users besides increment the likelihood of road accidents.[30]

- Price increases: Consumption by ane party causes prices to rise and therefore makes other consumers worse off, peradventure by preventing, reducing or delaying their consumption. These effects are sometimes chosen "pecuniary externalities" and are distinguished from "real externalities" or "technological externalities". Pecuniary externalities announced to exist externalities, but occur within the market mechanism and are non considered to be a source of market failure or inefficiency, although they may still result in substantial harm to others.[31]

- Weak public infrastructure, air pollution, climate modify, piece of work misallocation, resource requirements and land/space requirements equally in the externalities of automobiles.[32]

Positive [edit]

A positive externality (likewise called "external do good" or "external economy" or "beneficial externality") is the positive effect an activity imposes on an unrelated third party.[33] Similar to a negative externality, it can arise either on the production side, or on the consumption side.[19]

Positive production externality

A positive product externality occurs when a firm'due south product increases the well-being of others but the business firm is uncompensated by those others, while a positive consumption externality occurs when an individual's consumption benefits other merely the individual is uncompensated by those others.[34]

Positive production externalities [edit]

Examples of positive production externalities

- A beekeeper who keeps the bees for their beloved. A side issue or externality associated with such activity is the pollination of surrounding crops by the bees. The value generated by the pollination may exist more important than the value of the harvested dearest.

- The corporate development of some free software (studied notably by Jean Tirole and Steven Weber[35])

- Research and development, since much of the economical benefits of research aren't captured by the originating firm.[36]

- An industrial company providing first assist classes for employees to increase on the job safety. This may also relieve lives outside the factory.

- Restored historic buildings may encourage more people to visit the surface area and patronize nearby businesses.[37]

- A foreign firm that demonstrates upward-to-date technologies to local firms and improves their productivity.[38]

Positive consumption externality

Positive consumption externalities [edit]

Examples of positive consumption externalities include:

- An individual who maintains an attractive house may confer benefits to neighbors in the grade of increased marketplace values for their backdrop. This is an instance of a pecuniary externality, because the positive spillover is accounted for in market prices. In this case, house prices in the neighborhood will increment to match the increased real estate value from maintaining their aesthetic. (such equally by mowing the lawn, keeping the trash orderly, and getting the firm painted) [39]

- An private receiving a vaccination for a communicable disease not just decreases the likelihood of the private'due south own infection, just also decreases the likelihood of others condign infected through contact with the individual. (Meet herd immunity)

- Increased didactics of individuals, as this can atomic number 82 to broader society benefits in the form of greater economic productivity, a lower unemployment rate, greater household mobility and college rates of political participation.[forty]

- An individual buying a production that is interconnected in a network (e.m., a smartphone). This will increase the usefulness of such phones to other people who have a video cellphone. When each new user of a product increases the value of the same product endemic by others, the miracle is called a network externality or a network effect. Network externalities often take "tipping points" where, suddenly, the product reaches full general acceptance and near-universal usage.

- In an area that does non have a public burn down department, homeowners who purchase individual fire protection services provide a positive externality to neighboring backdrop, which are less at risk of the protected neighbor's fire spreading to their (unprotected) firm.

Collective solutions or public policies are implemented to regulate activities with positive or negative externalities.

Positional [edit]

Positional externalities are also called Pecuniary externalities. These externalities "occur when new purchases alter the relevant context within which an existing positional good is evaluated."[41] Robert H. Frank gives the following example:

- if some job candidates brainstorm wearing expensive custom-tailored suits, a side event of their action is that other candidates get less likely to make favorable impressions on interviewers. From any individual job seeker's point of view, the best response might be to lucifer the college expenditures of others, lest her chances of landing the job fall. But this outcome may be inefficient since when all spend more, each candidate's probability of success remains unchanged. All may concord that some form of collective restraint on expenditure would be useful."[41]

Frank notes that treating positional externalities like other externalities might pb to "intrusive economic and social regulation."[41] He argues, however, that less intrusive and more efficient means of "limiting the costs of expenditure cascades"—i.e., the hypothesized increment in spending of middle-income families across their means "because of indirect effects associated with increased spending by top earners"—exist; i such method is the personal income tax.[41]

Inframarginal [edit]

The concept of inframarginal externalities was introduced by James Buchanan and Craig Stubblebine in 1962.[42] Inframarginal externalities differ from other externalities in that there is no benefit or loss to the marginal consumer. At the relevant margin to the market, the externality does not affect the consumer and does not cause a market inefficiency. The externality merely affects at the inframarginal range outside where the market clears. These types of externalities do not crusade inefficient allocation of resource and do not require policy activity.

Technological [edit]

Technological externalities directly touch on a house's production and therefore, indirectly influence an private'southward consumption; and the overall bear upon of lodge; for example Open-source software or free software evolution by corporations.

Supply and need diagram [edit]

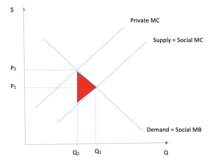

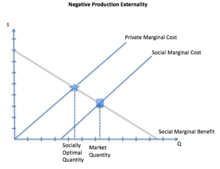

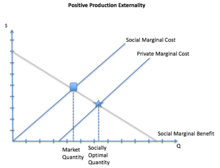

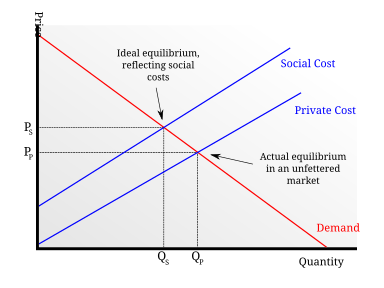

The usual economic assay of externalities tin can exist illustrated using a standard supply and demand diagram if the externality can be valued in terms of money. An extra supply or need curve is added, every bit in the diagrams beneath. One of the curves is the individual cost that consumers pay as individuals for boosted quantities of the good, which in competitive markets, is the marginal private cost. The other curve is the true cost that guild equally a whole pays for production and consumption of increased production the skilful, or the marginal social cost. Similarly, there might be two curves for the need or do good of the practiced. The social demand curve would reflect the benefit to society as a whole, while the normal demand curve reflects the benefit to consumers as individuals and is reflected as effective need in the market.

What curve is added depends on the type of externality that is described, but not whether it is positive or negative. Whenever an externality arises on the product side, there will be 2 supply curves (private and social toll). However, if the externality arises on the consumption side, there will exist two demand curves instead (individual and social benefit). This distinction is essential when it comes to resolving inefficiencies that are caused by externalities.

External costs [edit]

Demand curve with external costs; if social costs are not accounted for price is besides low to cover all costs and hence quantity produced is unnecessarily loftier (because the producers of the good and their customers are essentially underpaying the total, existent factors of production.)

The graph shows the furnishings of a negative externality. For instance, the steel industry is assumed to exist selling in a competitive market – before pollution-control laws were imposed and enforced (e.g. under laissez-faire). The marginal private cost is less than the marginal social or public cost by the corporeality of the external price, i.e., the cost of air pollution and water pollution. This is represented by the vertical distance betwixt the 2 supply curves. It is assumed that there are no external benefits, and then that social benefit equals individual benefit.

If the consumers only take into account their ain private price, they volition finish up at price Pp and quantity Qp , instead of the more efficient price Ps and quantity Qs . These latter reflect the thought that the marginal social benefit should equal the marginal social price, that is that production should be increased simply as long as the marginal social benefit exceeds the marginal social toll. The result is that a free market is inefficient since at the quantity Qp , the social benefit is less than the social price, so order as a whole would be better off if the goods betwixt Qp and Qs had not been produced. The problem is that people are buying and consuming also much steel.

This discussion implies that negative externalities (such every bit pollution) are more than but an ethical problem. The problem is one of the disjunctures between marginal individual and social costs that are not solved by the free market. It is a problem of societal communication and coordination to residuum costs and benefits. This also implies that pollution is not something solved by competitive markets. Some collective solution is needed, such as a court system to let parties affected by the pollution to be compensated, government intervention banning or discouraging pollution, or economic incentives such as green taxes.

External benefits [edit]

Supply curve with external benefits; when the marketplace does not account for the boosted social benefits of a adept both the price for the good and the quantity produced are lower than the market could bear.

The graph shows the effects of a positive or beneficial externality. For example, the industry supplying smallpox vaccinations is assumed to be selling in a competitive market. The marginal individual benefit of getting the vaccination is less than the marginal social or public do good by the amount of the external benefit (for example, society as a whole is increasingly protected from smallpox by each vaccination, including those who refuse to participate). This marginal external benefit of getting a smallpox shot is represented by the vertical distance between the two demand curves. Assume there are no external costs, so that social price equals private cost.

If consumers just take into account their own private benefits from getting vaccinations, the market will end up at price Pp and quantity Qp every bit before, instead of the more than efficient toll Psouth and quantity Qs . This latter once again reflect the thought that the marginal social benefit should equal the marginal social price, i.e., that production should be increased as long as the marginal social benefit exceeds the marginal social price. The result in an unfettered market is inefficient since at the quantity Qp , the social benefit is greater than the societal price, so guild as a whole would be better off if more than goods had been produced. The trouble is that people are buying likewise few vaccinations.

The result of external benefits is related to that of public goods, which are goods where it is difficult if not impossible to exclude people from benefits. The product of a public skillful has beneficial externalities for all, or most all, of the public. As with external costs, at that place is a problem here of societal communication and coordination to balance benefits and costs. This also implies that vaccination is non something solved by competitive markets. The authorities may take to step in with a collective solution, such as subsidizing or legally requiring vaccine use. If the government does this, the good is called a merit practiced. Examples include policies to accelerate the introduction of electric vehicles[43] or promote cycling,[44] both of which do good public health.

Causes [edit]

Externalities often arise from poorly defined belongings rights. While belongings rights to some things, such as objects, land, and money can be easily divers and protected, air, h2o, and wild animals often flow freely across personal and political borders, making it much more difficult to assign ownership. This incentivizes agents to consume them without paying the full cost, leading to negative externalities. Positive externalities similarly accrue from poorly defined holding rights. For example, a person who gets a flu vaccination cannot ain part of the herd amnesty this confers on society, so they may choose not to be vaccinated.

Another common cause of externalities is the presence of transaction costs.[45] Transaction costs are the toll of making an economic trade. These costs preclude economic agents from making exchanges they should be making. The costs of the transaction outweigh the benefit to the agent. When not all mutually beneficial exchanges occur in a market place, that market is inefficient. Without transaction costs, agents could freely negotiate and internalize all externalities.

Possible solutions [edit]

Solutions in non-market economies [edit]

- In planned economies, product is typically limited only to necessity, which would eliminate externalities created by overproduction.

- The central planner can determine to create and classify jobs in industries that piece of work to mitigate externalities, rather than waiting for the marketplace to create a need for these jobs.

Solutions in market economies [edit]

There are several general types of solutions to the problem of externalities, including both public- and private-sector resolutions:

- Corporations or partnerships will allow confidential sharing of information among members, reducing the positive externalities that would occur if the data were shared in an economy consisting but of individuals.

- Pigovian taxes or subsidies intended to redress economic injustices or imbalances.

- Regulation to limit activity that might cause negative externalities

- Government provision of services with positive externalities

- Lawsuits to compensate affected parties for negative externalities

- Voting to cause participants to internalize externalities subject to the weather of the efficient voter dominion.[46]

- Mediation or negotiation between those affected by externalities and those causing them

A Pigovian tax (also called Pigouvian tax, after economist Arthur C. Pigou) is a tax imposed that is equal in value to the negative externality. In guild to fully correct the negative externality, the per unit tax should equal the marginal external cost.[47] The upshot is that the market upshot would be reduced to the efficient corporeality. A side upshot is that acquirement is raised for the government, reducing the amount of distortionary taxes that the government must impose elsewhere. Governments justify the use of Pigovian taxes saying that these taxes help the market achieve an efficient result because this tax bridges the gap between marginal social costs and marginal private costs.[48]

Some arguments against Pigovian taxes say that the tax does non business relationship for all the transfers and regulations involved with an externality. In other words, the tax only considers the amount of externality produced.[49] Another argument against the tax is that it does not take private property into consideration. Under the Pigovian system, 1 firm, for example, tin be taxed more than another firm, even though the other firm is actually producing greater amounts of the negative externality.[50]

Farther arguments against Pigou disagree with his supposition every externality has someone at fault or responsible for the amercement.[51] Coase argues that externalities are reciprocal in nature. Both parties must be nowadays for an externality to exist. He uses the example of two neighbors. One neighbour possesses a fireplace, and ofttimes lights fires in his firm without issue. Then one day, the other neighbor builds a wall that prevents the smoke from escaping and sends it back into the fire-building neighbour's home. This illustrates the reciprocal nature of externalities. Without the wall, the smoke would non exist a problem, but without the fire, the smoke would not exist to cause problems in the first place. Coase as well takes consequence with Pigou's assumption of a "chivalrous despot" authorities. Pigou assumes the government's role is to see the external costs or benefits of a transaction and assign an advisable tax or subsidy. Coase argues that the government faces costs and benefits just like whatsoever other economic agent, so other factors play into its controlling.

Even so, the virtually mutual type of solution is a tacit agreement through the political procedure. Governments are elected to stand for citizens and to strike political compromises between various interests. Commonly governments pass laws and regulations to address pollution and other types of environmental impairment. These laws and regulations can take the course of "control and control" regulation (such as setting standards, targets, or process requirements), or environmental pricing reform (such as ecotaxes or other Pigovian taxes, tradable pollution permits or the creation of markets for ecological services). The second type of resolution is a purely individual agreement between the parties involved.

Government intervention might not ever exist needed. Traditional ways of life may have evolved as means to bargain with external costs and benefits. Alternatively, democratically run communities can concur to deal with these costs and benefits in an amicable way. Externalities can sometimes be resolved by agreement betwixt the parties involved. This resolution may even come about because of the threat of government activity.

The use of taxes and subsidies in solving the problem of externalities Correction tax, respectively subsidy, ways essentially any mechanism that increases, respectively decreases, the costs (and thus price) associated with the activities of an individual or company.[52]

The private-sector may sometimes be able to bulldoze guild to the socially optimal resolution. Ronald Coase argued that an efficient issue can sometimes be reached without government intervention. Some have this statement further, and make the political statement that government should restrict its part to facilitating bargaining amidst the affected groups or individuals and to enforcing whatever contracts that outcome.

This result, ofttimes known as the Coase theorem, requires that

- Property rights be well-divers

- People act rationally

- Transaction costs be minimal (gratuitous bargaining)

- Complete information

If all of these conditions apply, the private parties can bargain to solve the problem of externalities. The second part of the Coase theorem asserts that, when these conditions hold, whoever holds the belongings rights, a Pareto efficient upshot will be reached through bargaining.

This theorem would not use to the steel industry case discussed above. For example, with a steel factory that trespasses on the lungs of a large number of individuals with pollution, information technology is hard if non impossible for any 1 person to negotiate with the producer, and there are big transaction costs. Hence the most common arroyo may be to regulate the firm (by imposing limits on the corporeality of pollution considered "acceptable") while paying for the regulation and enforcement with taxes. The case of the vaccinations would as well not satisfy the requirements of the Coase theorem. Since the potential external beneficiaries of vaccination are the people themselves, the people would have to cocky-organize to pay each other to be vaccinated. But such an organization that involves the unabridged populace would be indistinguishable from government activity.

In some cases, the Coase theorem is relevant. For case, if a logger is planning to clear-cut a forest in a mode that has a negative bear upon on a nearby resort, the resort-owner and the logger could, in theory, go together to agree to a deal. For example, the resort-owner could pay the logger non to clear-cut – or could buy the forest. The nigh problematic state of affairs, from Coase's perspective, occurs when the forest literally does not belong to anyone, or in any example in which there are non well-divers and enforceable belongings rights; the question of "who" owns the forest is not of import, as whatever specific owner will accept an interest in coming to an agreement with the resort owner (if such an agreement is mutually beneficial).

All the same, the Coase theorem is difficult to implement considering Coase does non offer a negotiation method.[53] Moreover, Coasian solutions are unlikely to be reached due to the possibility of running into the assignment problem, the holdout problem, the free-rider trouble, or transaction costs. Additionally, firms could potentially bribe each other since there is piffling to no government interaction under the Coase theorem.[54] For instance, if one oil business firm has a high pollution rate and its neighboring firm is bothered by the pollution, and then the latter firm may move depending on incentives. Thus, if the oil house were to bribe the 2d firm, the first oil business firm would suffer no negative consequences because the authorities would non know virtually the bribing.

In a dynamic setup, Rosenkranz and Schmitz (2007) have shown that the impossibility to rule out Coasean bargaining tomorrow may actually justify Pigouvian intervention today.[55] To see this, note that unrestrained bargaining in the hereafter may atomic number 82 to an underinvestment problem (the so-called hold-up problem). Specifically, when investments are relationship-specific and non-contractible, then insufficient investments will be fabricated when it is anticipated that parts of the investments' returns will go to the trading partner in futurity negotiations (encounter Hart and Moore, 1988).[56] Hence, Pigouvian revenue enhancement tin can be welfare-improving precisely considering Coasean bargaining will have place in the future. Antràs and Staiger (2012) make a related point in the context of international merchandise.[57]

Kenneth Pointer suggests another individual solution to the externality problem.[58] He believes setting upward a market for the externality is the reply. For example, suppose a firm produces pollution that harms another firm. A competitive market for the right to pollute may permit for an efficient issue. Firms could bid the cost they are willing to pay for the amount they desire to pollute, and so have the right to pollute that amount without penalty. This would allow firms to pollute at the amount where the marginal cost of polluting equals the marginal benefit of another unit of pollution, thus leading to efficiency.

Frank Knight likewise argued against government intervention as the solution to externalities.[59] He proposed that externalities could be internalized with privatization of the relevant markets. He uses the instance of road congestion to brand his point. Congestion could be solved through the taxation of public roads. Knight shows that regime intervention is unnecessary if roads were privately endemic instead. If roads were privately owned, their owners could fix tolls that would reduce traffic and thus congestion to an efficient level. This statement forms the ground of the traffic equilibrium. This argument supposes that ii points are continued by 2 dissimilar highways. Ane highway is in poor condition, but is broad enough to fit all traffic that desires to use it. The other is a much better road, only has express capacity. Knight argues that, if a large number of vehicles operate between the two destinations and take liberty to choose between the routes, they volition distribute themselves in proportions such that the cost per unit of measurement of transportation will be the same for every truck on both highways. This is true considering as more trucks use the narrow road, congestion develops and as congestion increases it becomes equally profitable to use the poorer highway. This solves the externality issue without requiring any government taxation or regulations.

Solutions to greenhouse gas emission externalities [edit]

The negative effect of carbon emissions and other greenhouse gases produced in production exacerbate the numerous environmental and man impacts of anthropogenic climate change. These negative effects are not reflected in the toll of producing, nor in the market price of the final goods. There are many public and individual solutions proposed to gainsay this externality

Emissions fee [edit]

An emissions fee, or carbon tax, is a tax levied on each unit of pollution produced in the production of a good or service. The tax incentivised producers to either lower their production levels or to undertake abatement activities that reduce emissions by switching to cleaner engineering science or inputs.[60]

Cap-and-trade systems [edit]

The cap-and-trade organisation enables the efficient level of pollution (determined by the government) to be achieved by setting a full quantity of emissions and issuing tradable permits to polluting firms, allowing them to pollute a certain share of the permissible level. Permits will exist traded from firms that have depression abatement costs to firms with higher abatement costs and therefore the system is both price-effective and cost-efficient. The cap and merchandise system has some practical advantages over an emissions fee such as the fact that: 1. it reduces uncertainty about the ultimate pollution level. 2. If firms are profit maximizing, they will utilize cost-minimizing applied science to attain the standard which is efficient for individual firms and provides incentives to the research and development marketplace to innovate. 3. The market price of pollution rights would keep pace with the price level while the economy experiences aggrandizement.

The emissions fee and cap and trade systems are both incentive-based approaches to solving a negative externality problem. They provide polluters with market incentives by increasing the opportunity toll of polluting, thus forcing them to internalize the externality by making them take the marginal external damages of their product into account.[61]

Control-and-control regulations [edit]

Command-and-control regulations act as an alternative to the incentive-based approach. They require a set up quantity of pollution reduction and tin can take the form of either a technology standard or a performance standard. A technology standard requires pollution producing firms to apply specified applied science. While it may reduce the pollution, it is non cost-effective and stifles innovation by incentivising research and development for applied science that would work meliorate than the mandated ane. Performance standards set emissions goals for each polluting firm. The free selection of the firm to decide how to reach the desired emissions level makes this selection slightly more efficient than the technology standard, notwithstanding, it is not as cost-constructive as the cap-and-merchandise organisation since the brunt of emissions reduction cannot be shifted to firms with lower abatement.[62]

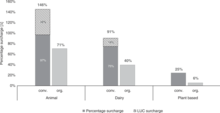

Scientific calculation of external costs [edit]

"Relative percentage price [∆] increases for wide categories [...] when externalities of greenhouse gas emissions are included in the producer's price."[63]

A 2020 scientific analysis of external climate costs of foods indicates that external greenhouse gas costs are typically highest for animal-based products – conventional and organic to about the aforementioned extent within that ecosystem-subdomain – followed past conventional dairy products and lowest for organic establish-based foods and concludes that contemporary monetary evaluations are "inadequate" and that policy-making that lead to reductions of these costs to be possible, advisable and urgent.[64] [65] [63]

Criticism [edit]

Ecological economics criticizes the concept of externality because there is not enough organization thinking and integration of different sciences in the concept. Ecological economic science is founded upon the view that the neoclassical economics (NCE) assumption that ecology and customs costs and benefits are mutually cancelling "externalities" is non warranted. Joan Martinez Alier,[66] for instance shows that the bulk of consumers are automatically excluded from having an impact upon the prices of bolt, as these consumers are futurity generations who accept non been born nevertheless. The assumptions behind time to come discounting, which assume that future appurtenances will be cheaper than present goods, has been criticized by Fred Pearce[67] and by the Stern Report (although the Stern report itself does employ discounting and has been criticized for this and other reasons by ecological economists such as Clive Spash).[68]

Apropos these externalities, some, like the eco-businessman Paul Hawken, argue an orthodox economic line that the merely reason why goods produced unsustainably are usually cheaper than appurtenances produced sustainably is due to a subconscious subsidy, paid by the non-monetized human surroundings, community or future generations.[69] These arguments are developed further by Hawken, Amory and Hunter Lovins to promote their vision of an environmental capitalist utopia in Natural Commercialism: Creating the Side by side Industrial Revolution.[70]

In contrast, ecological economists, like Joan Martinez-Alier, appeal to a unlike line of reasoning.[71] Rather than assuming some (new) form of capitalism is the all-time way forrard, an older ecological economic critique questions the very thought of internalizing externalities equally providing some corrective to the current organisation. The work by Karl William Kapp[72] argues that the concept of "externality" is a misnomer.[73] In fact the modern concern enterprise operates on the basis of shifting costs onto others as normal practice to make profits.[74] Charles Eisenstein has argued that this method of privatising profits while socialising the costs through externalities, passing the costs to the community, to the natural environment or to future generations is inherently destructive.[75] Social ecological economist Clive Spash argues that externality theory fallaciously assumes ecology and social bug are pocket-sized aberrations in an otherwise perfectly functioning efficient economic system.[76] Internalizing the odd externality does zippo to accost the structural systemic problem and fails to recognize the all pervasive nature of these supposed 'externalities'. This is precisely why heterodox economists argue for a heterodox theory of social costs to finer prevent the problem through the precautionary principle.[77]

Meet besides [edit]

- Coase theorem – Theorem in economic science

- CC–PP game – A theoretical concept in resource allocation to explicate economic decision-making

- Price externalizing

- Order good

- Externalities of automobiles

- Incentive compatibility

- Tragedy of the eatables – Cocky-interests causing depletion of a shared resource

- Unintended consequences – Unforeseen outcomes of an action

References [edit]

- ^ Gruber, J. (2018). Public Finance & Public Policy

- ^ a b Pigou, Arthur Cecil (2017-x-24), "Welfare and Economic Welfare", The Economics of Welfare, Routledge, pp. iii–22, doi:10.4324/9781351304368-1, ISBN978-1-351-30436-8 , retrieved 2020-11-03

- ^ Kolstad, Charles D.; Ulen, Thomas South.; Johnson, Gary V. (2018-01-12), "Ex Mail service Liability for Impairment vs. Ex Ante Condom Regulation: Substitutes or Complements?", The Theory and Practise of Command and Command in Environmental Policy, Routledge, pp. 331–344, doi:ten.4324/9781315197296-16, ISBN978-1-315-19729-6 , retrieved 2020-eleven-03

- ^ Kaplow, Louis (May 2012). "Optimal Control of Externalities in the Presence of Income Taxation". International Economical Review. 53 (2): 487–509. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2354.2012.00689.x. ISSN 0020-6598. S2CID 33103243.

- ^ Sim, Michael (2018). "Limited Liability and the Known Unknown". Duke Law Journal. 68: 275–332. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3121519. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 44186028 – via SSRN.

- ^ Hansmann, Henry; Kraakman, Reinier (May 1991). "Toward Unlimited Shareholder Liability for Corporate Torts". The Yale Law Journal. 100 (vii): 1879. doi:ten.2307/796812. ISSN 0044-0094. JSTOR 796812.

- ^ Buchanan, James; Wm. Craig Stubblebine (November 1962). "Externality". Economica. 29 (116): 371–84. doi:x.2307/2551386. JSTOR 2551386.

- ^ Mankiw, Nicholas (1998). Principios de Economía (Principles of Economics). Santa Fe: Cengage Learning. pp. 198–199. ISBN978-607-481-829-1.

- ^ "How do externalities affect equilibrium and create market failure?".

- ^ Gruber, Jonathan. Public Finance and Public Policy (6th ed.). Worth Publishers. p. 334. ISBN978-1-319-20584-3.

- ^ Stewart, Frances; Ghani, Ejaz (June 1991). "How pregnant are externalities for development?". Globe Evolution. 19 (six): 569–594. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(91)90195-North.

- ^ Jaeger, William. Environmental Economics for Tree Huggers and Other Skeptics, p. eighty (Isle Press 2012): "Economists oftentimes say that externalities need to be 'internalized,' pregnant that some action needs to be taken to correct this kind of marketplace failure."

- ^ "Economics (McConnell), 18th Edition Chapter 16: Public Appurtenances, Externalities, and Information Asymmetries".

- ^ Mas-Colell, Andreu (1995). Microeconomic Theory. Oxford. p. 878. ISBN978-0-nineteen-507340-9.

- ^ Laffont JJ. (1989) Externalities. In: Eatwell J., Milgate M., Newman P. (eds) Resource allotment, Information and Markets. The New Palgrave. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-20215-7_11

- ^ Caplan, Bryan. "Externalities". The Library of Economics and Freedom. Liberty Fund, Inc. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ William H. Sandholm, Negative Externalities and Evolutionary Implementation, The Review of Economic Studies, Book 72, Outcome iii, July 2005, Pages 885–915, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-937X.2005.00355.x

- ^ Rasure, E. (2020, December 29). Free Rider Problem. Retrieved from Investopedia: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/free_rider_problem.asp#:~:text=The%20free%20rider%20problem%20is,whatever%20community%2C%20large%20or%20small.

- ^ a b "Microeconomics – Externalities". Retrieved 2014-xi-23 .

- ^ Goodstein, Eban (2014-01-21). Economic science and the Environment. Wiley. p. 32. ISBN9781118539729.

- ^ Barry Commoner "Frail Reeds in a Harsh World". New York: The American Museum of Natural History. Natural History. Periodical of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. LXXVIII No. 2, February, 1969, p. 44

- ^ Torfs R, Int Panis Fifty, De Nocker L, Vermoote S (2004). Peter Bickel, Rainer Friedrich (eds.). "Externalities of Energy Methodology 2005 Update Other impacts: ecosystems and biodiversity". EUR 21951 EN – Extern E. European Commission Publications Part, Luxembourg: 229–37.

- ^ Rabl A, Hurley F, Torfs R, Int Panis L, De Nocker L, Vermoote South, Bickel P, Friedrich R, Droste-Franke B, Bachmann T, Gressman A, Tidblad J (2005). "Affect pathway Arroyo Exposure – Response functions" (PDF). In Peter Bickel, Rainer Friedrich (eds.). Externalities of Energy Methodology 2005 Update. Grand duchy of luxembourg: European Commission Publications Office. pp. 75–129. ISBN978-92-79-00423-0.

- ^ Stern, Nicholas (2006). "Introduction". The Economics of Climate Change The Stern Review (PDF). Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN978-0-521-70080-1.

- ^ Rao, Justin M; Reiley, David H (August 2012). "The Economics of Spam". Periodical of Economic Perspectives. 26 (3): 87–110. doi:ten.1257/jep.26.3.87.

- ^ White, Lawrence J.; McKenzie, Joseph; Cole, Rebel A. (3 November 2008). "Deregulation Gone Amiss: Moral Hazard in the Savings and Loan Manufacture". SSRN 1293468.

- ^ De Bandt, O.; Hartmann, P. (1998). "Risk Measurement and Systemic Risk" (PDF). Imes.boj.or.jp: 37–84.

- ^ Weiss, Rick (2008-04-30). "Report Targets Costs Of Manufactory Farming". Washington Post.

- ^ Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Product. "Proc Putting Meat on The Tabular array: Industrial Farm Animate being Production in America". The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg Schoolhouse of Public Health. .

- ^ Small, Kenneth A.; José A. Gomez-Ibañez (1998). Road Pricing for Congestion Management: The Transition from Theory to Policy. The University of California Transportation Center, University of California at Berkeley. p. 213.

- ^ Liebowitz, Southward. J; Margolis, Stephen East (May 1994). "Network Externality: An Uncommon Tragedy". Journal of Economic Perspectives. eight (2): 133–150. doi:10.1257/jep.8.2.133.

- ^ Gössling, Stefan; Kees, Jessica; Litman, Todd (one Apr 2022). "The lifetime cost of driving a car". Ecological Economics. 194: 107335. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107335. ISSN 0921-8009.

- ^ Varian, H.R. (2010). Intermediate microeconomics: a mod approach. New York, NY: Due west.W. Norton & Co.

- ^ Gruber, J. (2010) Public Finance and Public Policy, Worth Publishers. G-8 (Glossary)

- ^ The success of open up source Steven Weber, 2006 Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01292-5.

- ^ "Externalities - Definition and examples". Conceptually . Retrieved 26 Jan 2021.

- ^ Romero '05, Ana Maria (1 January 2004). "The Positive Externalities of Historic District Designation". The Park Place Economist. 12 (1).

- ^ Iršová, Zuzana; Havránek, Tomáš (Feb 2013). "Determinants of Horizontal Spillovers from FDI: Evidence from a Large Meta-Analysis". World Development. 42: 1–15. doi:ten.1016/j.worlddev.2012.07.001.

- ^ Samwick. "What Pecuniary Externalities?". Economist's View . Retrieved 8 Nov 2020.

- ^ Weisbrod, Burton, 1962. External Benefits of Public Education, Princeton University[ page needed ]

- ^ a b c d Robert H. Frank, "Are Positional Externalities Different from Other Externalities Archived 2012-12-21 at the Wayback Machine? " (draft for presentation for Why Inequality Matters: Lessons for Policy from the Economics of Happiness, Brookings Establishment, Washington, D.C., June 4–v, 2003).

- ^ Liebowitz, S.J.; Margolis, Stephen E., "Network Externality: An Uncommon Tragedy", Journal of Economic Perspectives, pp. 133–150

- ^ Buekers, Jurgen; Van Holderbeke, Mirja; Bierkens, Johan; Int Panis, Luc (Dec 2014). "Wellness and ecology benefits related to electric vehicle introduction in EU countries". Transportation Research Function D: Transport and Surround. 33: 26–38. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2014.09.002.

- ^ Buekers, Jurgen; Dons, Evi; Elen, Bart; Int Panis, Luc (December 2015). "Wellness impact model for modal shift from car use to cycling or walking in Flanders: application to two wheel highways". Journal of Transport & Health. two (4): 549–562. doi:x.1016/j.jth.2015.08.003.

- ^ Dahlman, Carl J., "The Problem of Externality", The Journal of Law & Economic science, pp. 141–162

- ^ Anderson, David A. (2020). "Ecology Exigencies and the Efficient Voter Dominion". Economies. eight (four): vii. doi:10.3390/economies8040100.

- ^ Gruber, Jonathan. Public Finance and Public Policy. Worth Publishers. pp. 364–365. ISBN978-1-319-20584-3.

- ^ Barthold, Thomas A. (1994). "Issues in the Blueprint of Excise Tax." Journal of Economic Perspectives. 133–51.

- ^ Nye, John (2008). "The Pigou Problem." The Cato Institute. 32–36.

- ^ Barnett, A. H.; Yandle, Bruce (24 June 2009). "The end of the externality revolution". Social Philosophy and Policy. 26 (2): 130–fifty. doi:x.1017/S0265052509090190. S2CID 154357550.

- ^ Coase, R.H. (1960). "The Trouble of Social Cost." The Periodical of Police and Economics. 1-44.

- ^ Journal of Mathematical Economic science (volume 44 ed.). February-2008. pp. 367–382.

- ^ Varian, Hal (1994). "A Solution to the Problem of Externalities When Agents Are Well Informed." The American Economic Review. Vol. 84 No. 5.

- ^ Marney, Thou.A. (1971). "The 'Coase Theorem:' A Reexamination." Quarterly Journal of Economics.Vol. 85 No. 4. 718–23.

- ^ Rosenkranz, Stephanie; Schmitz, Patrick Westward. (2007). "Tin can Coasean Bargaining Justify Pigouvian Taxation?". Economica. 74 (296): 573–585. doi:x.1111/j.1468-0335.2006.00556.x. hdl:10419/22952. ISSN 0013-0427. S2CID 154310004.

- ^ Hart, Oliver; Moore, John (1988). "Incomplete Contracts and Renegotiation" (PDF). Econometrica. 56 (4): 755–785. doi:10.2307/1912698. hdl:1721.one/63746. JSTOR 1912698.

- ^ Antràs, Politician; Staiger, Robert W (December 2012). "Offshoring and the Function of Trade Agreements" (PDF). American Economic Review. 102 (vii): 3140–3183. doi:ten.1257/aer.102.seven.3140.

- ^ Arrow, Kenneth, "Political and Economical Evaluation of Social Effects and Externalities", The Analysis of Public Output, pp. 1–thirty

- ^ Knight, Frank H., "Some Fallacies in the Interpretation of Social Cost", Quarterly Periodical of Economics, pp. 582–606

- ^ "Carbon Tax Basics". 20 October 2017.

- ^ "How cap and merchandise works".

- ^ "Command-and-command regulation (Article)".

- ^ a b Pieper, Maximilian; Michalke, Amelie; Gaugler, Tobias (xv December 2020). "Calculation of external climate costs for food highlights inadequate pricing of brute products". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 6117. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.6117P. doi:ten.1038/s41467-020-19474-6. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC7738510. PMID 33323933.

Available under CC By iv.0.

Available under CC By iv.0. - ^ Carrington, Damian (23 December 2020). "Organic meat product just as bad for climate, study finds". The Guardian . Retrieved xvi January 2021.

- ^ "Organic meats constitute to have approximately the same greenhouse touch on as regular meats". phys.org . Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Costanza, Robert; Segura, Olman; Olsen, Juan Martinez-Alier (1996). Getting Down to Earth: Practical Applications of Ecological Economics . Washington, D.C.: Isle Printing. ISBN978-1559635035.

- ^ Pearce, Fred "Blueprint for a Greener Economic system"

- ^ "Spash, C. L. (2007) The economics of climate change impacts à la Stern: Novel and nuanced or rhetorically restricted? Ecological Economics 63(4): 706–xiii" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2012-12-23 .

- ^ Hawken, Paul (1994) "The Environmental of Commerce" (Collins)

- ^ Hawken, Paul; Amory and Hunter Lovins (2000) "Natural Capitalism: Creating the Side by side Industrial Revolution" (Dorsum Bay Books)

- ^ Martinez-Alier, Joan (2002) The Environmentalism of the Poor: A Study of Ecological Conflicts and Valuation. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar

- ^ Berger, Sebastian (2017). The Social Costs of Neoliberalism: Essays on the Economic science of K. William Kapp. Nottingham: Spokesman.

- ^ Kapp, Karl William (1963) The Social Costs of Business Enterprise. Bombay/London, Asia Publishing House.[ page needed ]

- ^ Kapp, Karl William (1971) Social costs, neo-classical economics and environmental planning. The Social Costs of Business organisation Enterprise, 3rd edition. Grand. W. Kapp. Nottingham, Spokesman: 305–eighteen

- ^ Einsentein, Charles (2011), "Sacred Economics: Money, Souvenir and Gild in an Age in Transition" (Evolver Editions)

- ^ Spash, Clive 50. (June 2010). "The Brave New World of Carbon Trading" (PDF). New Political Economy. 15 (ii): 169–195. doi:ten.1080/13563460903556049. S2CID 44071002.

- ^ Berger, Sebastian (ed) (2015). The Heterodox Theory of Social Costs by Chiliad. William Kapp. London: Routledge.[ folio needed ]

Further reading [edit]

- Anderson, David A. (2019) Environmental Economics and Natural Resource Direction 5e, [1] New York: Routledge.

- Berger, Sebastian (2017) The Social Costs of Neoliberalism: Essays in the Economics of G. William Kapp. Nottingham: Spokesman.

- Berger, Sebastian (ed) (2015) The Heterodox Theory of Social Costs - by K. William Kapp. London: Routledge.

- Baumol, W. J. (1972). "On Taxation and the Command of Externalities". American Economic Review. 62 (3): 307–22. JSTOR 1803378.

- Johnson, Paul K. Definition "A Glossary of Economic Terms"

- Pigou, A.C. (1920). Economic science of Welfare. Macmillan and Co.

- Tullock, G. (2005). Public Appurtenances, Redistribution and Rent Seeking. Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. ISBN978-i-84376-637-vii.

- Volokh, Alexander (2008). "Externalities". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 162–63. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n101. ISBN978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Weitzman, Martin (October 1974). "Prices vs. Quantities". The Review of Economical Studies. 41 (4): 477–91. doi:10.2307/2296698. JSTOR 2296698. S2CID 153209646.

- Jean-Jacques Laffont (2008) Externalities. In: Palgrave Macmillan (eds) The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London

External links [edit]

- ExternE – European Wedlock project to evaluate external costs

- Econ 120 – Externalities

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Externality

Posted by: duongshateriere.blogspot.com

![{\displaystyle \theta _{i}\sim F_{i}[0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f74d88dc5a74267abb7454b585048cb2f72947d3)

![{\displaystyle \theta \in [0,1]^{N}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/170540af7ee06c63abe5aa8b871e05b2f80db2e4)

![{\displaystyle \kappa \colon [0,1]^{N}\to K}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/59dab43eefe325027bd5d1fc79e77dcd107b3eb7)

![{\displaystyle \theta =(\theta _{1},\ldots ,\theta _{N})\in [0,1]^{N}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/774e7a14b49ee31e1c884614ef945d9d6a984e60)

0 Response to "Which Would Be A Positive Externality Of A Landscaperã¢â‚¬â„¢s Service For An Individual Homeowner?"

Post a Comment